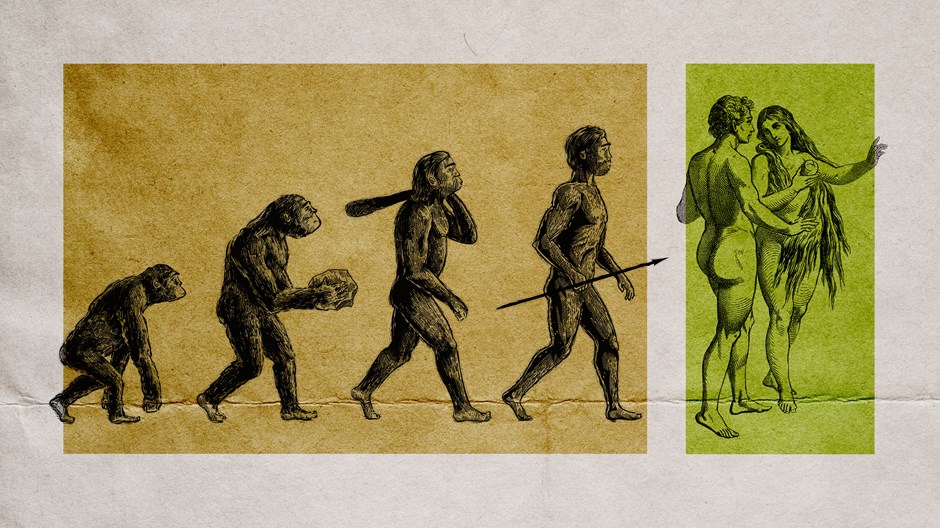

Ever since Charles Darwin proposed his theory of evolution, Christians have struggled to locate Adam and Eve within an evolutionary past. According to the traditional reading of the first chapters of Genesis, God created Adam and Eve directly and all human beings descended from that first couple. Yet many Christians have discarded this belief on the basis of evolutionary science, which holds that human beings, having descended from animals, first appeared on earth as a population rather than a single, divinely created pair.

S. Joshua Swamidass, a computational biologist at Washington University in St. Louis, wants to change the terms of this contentious debate. In his book, The Genealogical Adam and Eve: The Surprising Science of Universal Ancestry, Swamidass affirms both evolution and the traditional reading of the Genesis creation account. Drawing on findings from his field of computational biology, he contends that the lineage of Adam and Eve should be traced using genealogy rather than genetics. Viewing the origins debate through a genealogical prism, Swamidass presents a scenario in which the special creation of Adam and Eve thousands of years ago happens on a parallel track with evolution.

The Genealogical Adam and Eve carries a wide range of endorsements from theologians, atheist biologists, and believing scientists from across the origins-debate spectrum. CT science editor Rebecca Randall interviewed Swamidass about how his ideas might open new avenues of conversation between science and theology.

What is your research background? How did you come to study the genealogy of Adam and Eve?

I was raised a young-Earth creationist, and I moved to understanding evolutionary science and seeing legitimacy to it. Now, I use artificial intelligence to explore science at the intersection of biology, chemistry, and medicine. As a computational biologist, one of the things I care about is understanding how what we’re learning from the human genome influences our understanding of human origins. Questions of ancestry and origins are one area of focus for me at Peaceful Science, the scholarly community I help lead.

Who is your audience? Who are you trying to reach: young-Earth creationists or evolutionary creationists?

There are three main audiences to whom I’m speaking. One audience is my secular colleagues in science. Most of them aren’t Christians, but they want to effectively engage the public, including the religious public.

The second is nontraditionalists, such as evolutionary creationists at organizations like BioLogos who have been pressing the scientific case against Adam and Eve for a long time. I’m really trying to encourage them to take a more welcoming approach to traditional theology.

The last group is traditionalists: people who feel committed to a traditional interpretation of Scripture. I’m inviting them to engage with evolutionary science. I realize that many of them think that evolution is a myth. That’s okay. We can still recognize together that evolutionary science isn’t actually in conflict with their beliefs.

Your research is about genealogy, not genetics. Could you explain the difference for those who might interchange those terms? Why is this so key?

There’s been a lot of conflict about how science expresses its understanding of Adam and Eve. It has to do with misunderstanding the word ancestor. We can understand it in the genetic sense, meaning someone we get our DNA from. Or we can mean it in a genealogical sense, meaning someone whose lineage we descend from.

Genetics works in a very nonintuitive way. For example, my parents are both equally 100 percent my genealogical ancestors, and the same is true with my grandparents and great-grandparents. But my parents are each only one half of my genetic ancestry; my grandparents are one quarter; my great-grandparents are one eighth. Genetic ancestry just dilutes to the point where the majority of our genealogical ancestors pass on no DNA.

Why is that important? Scripture doesn’t tell us about genetic ancestry. It does, however, tell us about genealogical ancestry. Historically, we’ve believed that Adam and Eve are the ancestors of everyone. We can ask: Does this mean genetic ancestors or genealogical ancestors? Well, Scripture can’t possibly be talking about genetic ancestry. It has to be talking about genealogical ancestry.

That recognition really opens up an immense amount of space for theology. As Christians, we’ve had a lot of anxiety over what science is telling us about Adam and Eve. But these conflicts are based on what science says about our genetic ancestors. If we focus on genealogical ancestors instead, there might be far less conflict than we first imagined.

Can you outline what evolutionary science has suggested about Adam and Eve up until your research?

My book doesn’t exist to challenge the evolutionary science. The two starting points are: Humans share common ancestry with the great apes. It really looks like God created us through a providentially governed process of common descent. The second idea is: It seems like there’s no moment when our ancestors drop down to a single couple in the last few hundred thousand years.

People have taken those starting points and concluded, first, that the human population never gets down to a single couple; and second, that Adam and Eve, if they existed, must have shown common ancestry with the great apes.

I know it’s a subtle distinction, but what exactly do we mean by human? And what exactly do we mean by ancestor?

If we keep straight what the science is actually saying, the story of Genesis could be true as literally as you could imagine it, with Adam being created by dust and God breathing into his nostrils and Eve being created from his rib. But evolution is happening outside the Garden, and there are people out there who God created in a different way and who end up intermingling with Adam and Eve’s descendants. It’s not actually in conflict with evolutionary science.

In the book, you write on what it means to be human according to science and what it means to be human according to theology. What are some of the possible answers to these questions?

In science, there are a whole range of answers. In a recent book called Adam and the Genome, there’s a commitment to saying that humans must be Homo sapiens. But that’s not even the consensus position of science. Some scientists use the term Homo sapiens to refer to our species, or they expand the Homo genus to include other species like Neanderthals, too. Thinking about humans in that way might just hide the most important part of the conversation under a false sense of certainty. Scientists cannot agree on a precise definition of our species or our genus. As we look back into our past, our vision grows murky.

In theology, sometimes human beings are defined as those made in the image of God. But theologians and interpreters of Scripture can’t find exact agreement what that means either. There are three main views on what it means to bear God’s image: the substantive, which refers to our capacity for thinking and feeling; the relational, which refers to our capacity to relate to one another and to God; and the vocational, which refers to our capacity to rule over creation. But those simple categorizations hide a lot of complexity and disagreement. Theologians are just as unsettled on the meaning of the image of God as scientists are on the meaning of human.

In my book, I suggest that one valid definition, from the point of view of Scripture, is to define human beings as Adam, Eve, and their descendants. There might be biological humans, fully human, outside the Garden, but Scripture is bound to the story of Adam, Eve, and their lineage. It is not talking about others, even if they have the same degree of biological humanness as us.

This leaves open lots of questions about the meaning of the image of God, the essentials of humanness, and how we think about the possibility of people existing outside the Garden. This possibility has been the subject of conversation for centuries. Scripture suggests they exist, but it’s like they appear in the peripheral vision. It’s a grand invitation for theologians to wonder together about who they could have been.

That’s one of the grand conversations. Let’s have that conversation.

One of the stickier parts of studying this history and thinking about populations living alongside Adam and Eve is that you’re forced to confront objections of racism in our understanding of these humans. What lessons have you learned from wrestling with this personally?

One thing I’ve learned is it’s really common for people to bring race into questions about human origins, often to attack those with whom they disagree. We all inherit that legacy of racism. Origins is often approached from a very whitewashed perspective. It doesn’t really engage the concerns of people of color, who are often underrepresented in the conversations. What I found, as a dark Indian, is that these questions of origins are actually very closely tied to our concerns about our worth and dignity in the world.

This conversation doesn’t have to be so whitewashed. There’s a real value in going back to that history of racism, to uncover it and work through it. There is an opportunity to work through our understanding of justice, mercy, and inheritance in a way that connects with the concerns of African Americans, Indians like myself, and many other people that are so underrepresented in the conversation.

The important thing to emphasize is that the science of origins is solidly against the idea of a biologically distinct race. This is something that really needs to be said more often. We have a better understanding of how we are all connected in one family. Genealogical science makes that clear.

All of the science that supported racism by arguing that we’re all disconnected populations—some of us descending from Adam and Eve, some of us not; some of us with certain biological abilities, and some of us not—that all turns out to be untrue. Some Christians were skeptical of evolution because it appeared to challenge the historical doctrine of monogenesis—the idea that all human beings descended from a single pair of ancestors. And it turns out that the rival theory, polygenesis, really is false.

Could you define polygenesis?

Polygenesis was a false theory of origins that was often conscripted to provide support for racism. It’s the idea that the humans alive today are divided into biological groups that have been separated in the past and have distinct biological abilities, different theological roles, and varying levels of rights and dignity. That’s just totally false. One of the main reasons people historically rejected evolutionary science is that it seemed to be teaching polygenesis. In fact, for about a century, many scientists would have endorsed that theory. Then, starting in the 1970s, several different lines of evidence cropped up to demonstrate that polygenesis is complete nonsense.

In light of your work, what are some ways that different viewpoints on human origins can come together?

This book reshuffles the deck in many ways. It isn’t a single model for Adam and Eve. Rather, it’s a retelling of the science of origins in a way that makes space for lots of differences. There’s more space in science than we’ve been led to believe.

People from all sides of the conversation are reconfiguring where they stand. There’s an opportunity for a new way forward, to make space for people to come to a less oppositional and more conversational relationship with mainstream science. That’s what to look forward to right now.

One fun question: Personally, I enjoy uncovering family history. I’ve connected with different genetic relatives over the years. What do you think about the rise in popularity of DNA kits? For those interested in ancestry, what can we be thinking about as Christians?

Keep in mind, if you go back a few thousand years, we all share the same family. As Christians, we know that our origins are important. But we also know that what we inherit is more than our DNA. As Christians we should be thinking more broadly about ancestry and specifically about our inheritance. What is it that we inherit—biologically, culturally, physically, societally? When we look at the question through these different lenses, we come upon a wealth of different understandings of things like original sin, justice, and race. We enter into a grand dialogue in theology that’s far richer than any DNA test would be.